Hot Blood & Cold Steel: game design

-

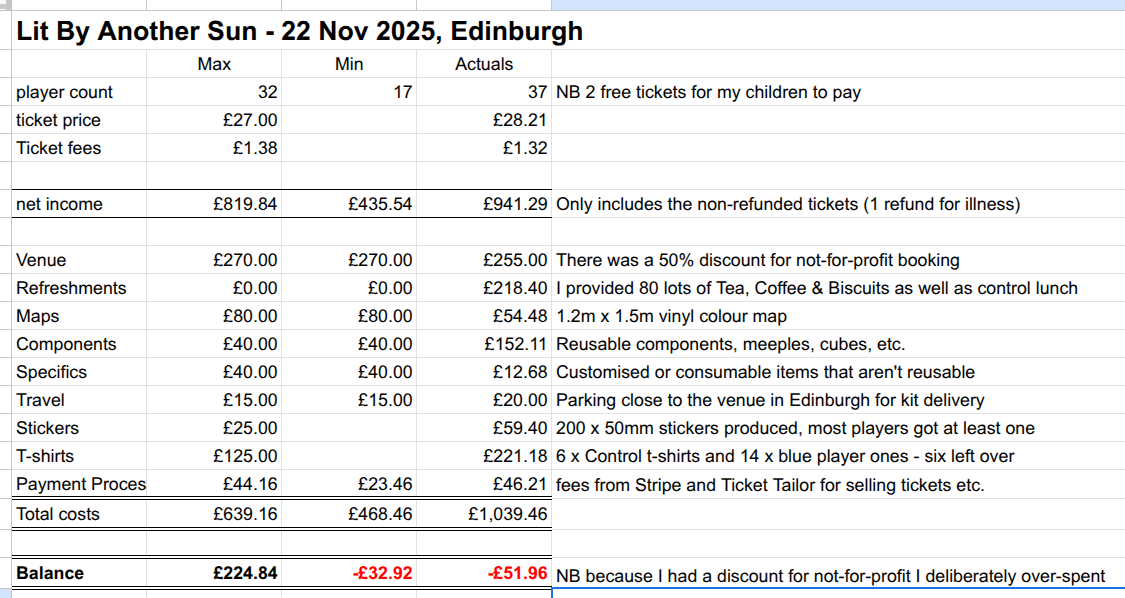

Megagame Costs – Worked Example

I’ve just run my first megagame, and there aren’t many places that show you how much a megagame costs to run. Most megagames are run by enthusiasts, and the costs seem to vary wildly from speaking to game runners. So I thought I’d keep some notes for my first megagame “Lit By Another Sun” which…

-

Lit By Another Sun – Tickets on Sale now

You can now get Lit By Another Sun tickets from Ticket Tailor. https://www.tickettailor.com/events/truenorthmegagames/1834618 Lit By Another Sun A megagame of space colonists and murky factions A realistic Sci-Fi game about establishing a new human Colony in the 23rd century. Inspired by The Expanse, Battlestar Galactica, and a lifetime of reading and watching SF. The game…

-

![By the Grace of God [Megagame]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/IMG_20191005_160129.jpg)

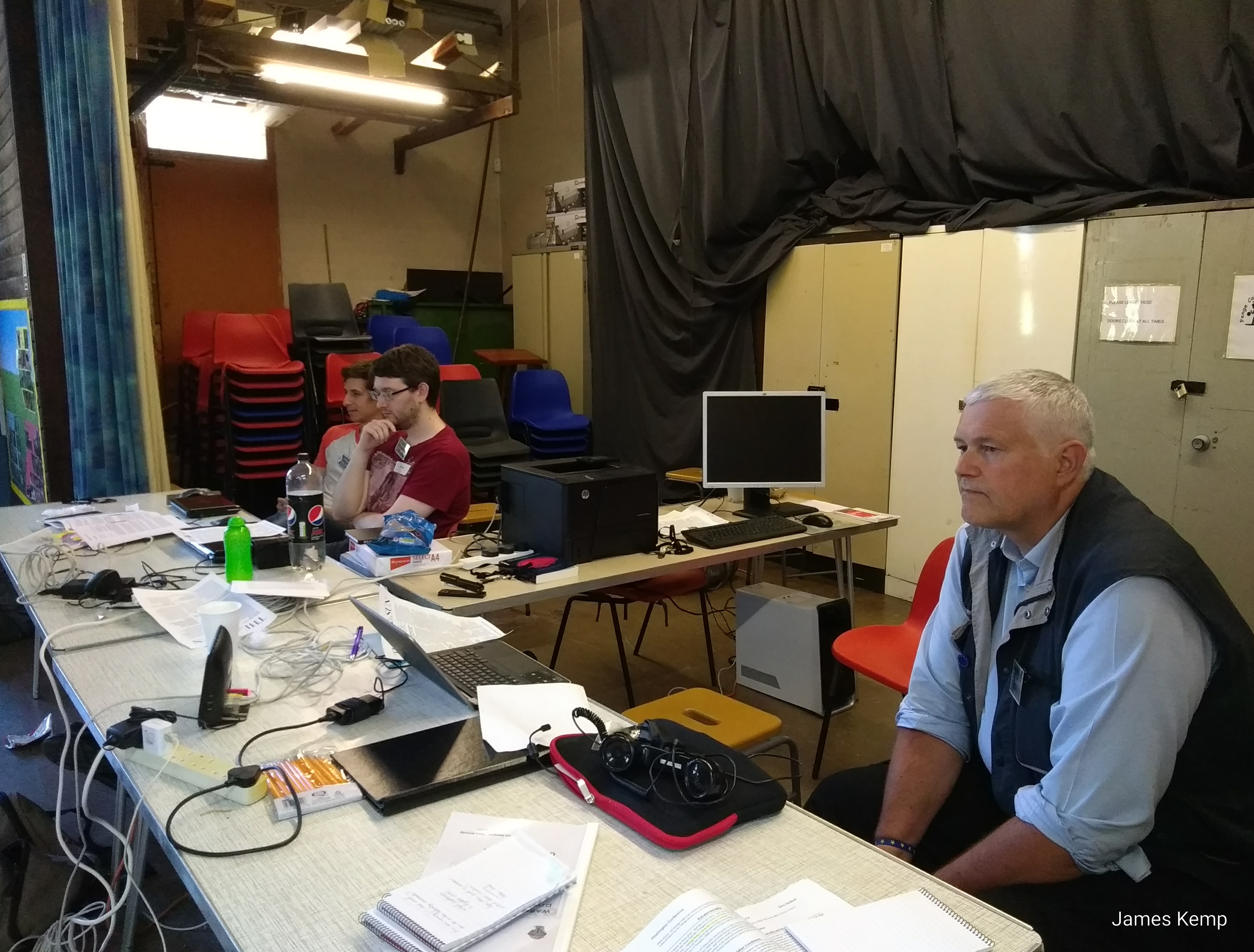

By the Grace of God [Megagame]

Today I played David Leslie, Admiral of the Scots Navy in By the Grace of God, a Megagame of the period at the end of the first of the civil wars in the 1640s. The game started in the Autumn of 1646 with the Covenanters in control of King Charles I, by the Grace of…

-

![Destructive & Formidable by David Blackmore [Book Review]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/dsc_0068.jpg)

Destructive & Formidable by David Blackmore [Book Review]

Destructive and Formidable by David Blackmore is a quantitative look at British infantry doctrine using period sources from the British Civil Wars of the seventeenth century up to just before the Napoleonic wars. If anything you can see the constancy, which drove the success in battle of British forces, even when outnumbered. Development of British…

-

Washington Conference Megagame Newspaper Reports

For his 70th birthday Dave Boundy decided to run his Washington Conference Megagame again. It’s at least the fourth time Washington Conference has been run as a Megagame. I’ve previously played as a Japanese Admiral, although this time I was one of the press team. Also, unlike recent megagames the entire cast list were veteran…

-

Blood and Thunder 4 – a Megagame of Pirates

Alexander and I played arms merchants in the Blood and Thunder 4 pirate megagame on Saturday. It was mostly a fun game, although there were a couple of sticky points for us as merchants. I was cast as Theophilus Blodwell, a Glaswegian on the run from the British Authorities. As well as being an arms…

-

Divided Land – Being a Terrorist in a Megagame

I played the leader of a terrorist organisation in the Divided Land megagame. Divided Land was about the situation in Palestine in 1947, we played from March through to an agreement on partition in August 1947. We then made plans on what would happen when the agreement came into force at 00:01 on 1st January…

-

ANDR – Autonomous Networked Dynamic-learning Robots

A conversation with my son over a McDonald’s sparked a bit of architecture for Autonomous Networked Dynamic-learning Robots (AKA ANDR) and a short story about their use in a near future counterinsurgency operation. You can read the short story (First Mission ANDR12) on my writing and reading blog. ANDR Requirements Being an analyst underneath and…

-

![Undeniable Victory – offside report [Megagame]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IMG_20171118_164040.jpg)

Undeniable Victory – offside report [Megagame]

Today I played in Undeniable Victory, Ben Moore’s megagame of the Iran Iraq War. I was an Iranian Radical and a member of the Council, starting off as the Procurement Minister responsible for buying military kit. Undeniable Victory I was a late entrant to Undeniable Victory, getting a place because someone else couldn’t make it.…

Got any book recommendations?

![Tokuemon Takedown [D&D 5e]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/IMG_20190707_142632.jpg)

![Silkworm Inn catches fire [D&D 5e]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/leaf-41641_1280.png)