Mass mobilisation for a world war level conflict would need the country to repeat what it did for WW1 & WW2.

Discussion I’ve read on twitter amongst those interested and knowledgable about defence (a mixture of serving officers, military historians and political observers) suggests that Britain has a real problem with the level of defence spending and decaying of capability for mass mobilisation to support a world war level conflict.

Years of small wars on the back of the 1990s ‘peace dividend’ has prevented major equipment changes. The British Army is still using many of the same armoured vehicles that it had in 1989. They’ve had internal upgrades, and improved control systems. The lighter vehicles have fared better because there were urgent operational requirements for Iraq and Afghanistan.

Mass mobilisation for World War 2

Britain was in a similar state to now in the early 30s. After WW1 we didn’t want to go to war again. The army was small and didn’t have any of their kit replaced. With few exceptions in 1933, when Hitler came to power, the British Army was using the same kit that it had ended the world war with in 1918. The recognition of the nazi threat lead to an abandoning of the ten year rule (where we funded our armed forces on the assumption there would be no major war for at least ten years).

Appeasement was a policy not of keeping Hitler happy, but of buying us time to re-equip and expand our armed forces in preparation for mass mobilisation. Through the late thirties a massive programme of expansion and re-equipment went on. In 1938 Britain spent 7.4% of GDP on Defence [1], which is three and a half times what we are spending now. This doubled in 1939 to 15.3% – not all of which was after the declaration of war in September. By 1941 it was above 50% and it stayed there for the duration.

Existential Threat

The nazis were seen as an existential threat, so the public were willing to support mass mobilisation for world war two and accept the sacrifice of additional taxes to pay for the war. Income tax doubled from a basic rate of 25%, which is similar to the current level. I think it would be fair to say that Britain could only afford mass mobilisation for world war three if we could see an existential threat to the country.

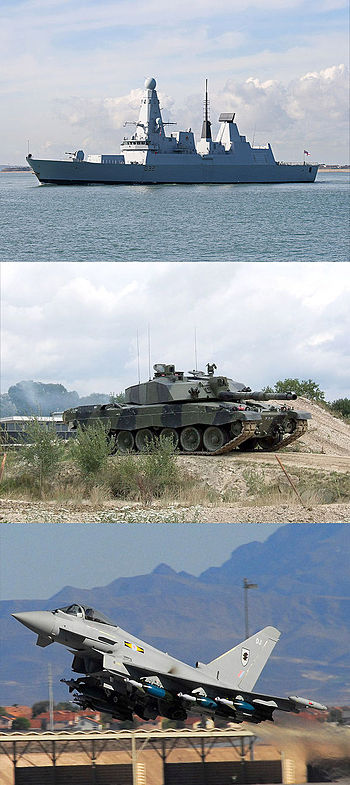

Without an existential threat, today we could field one armoured Division with air and naval support. We can’t move it anywhere in a hurry without hiring civilian cargo vessels. Against certain countries that division would be an annoyance, but it certainly wouldn’t stop them doing what they wanted, just impose a stiff price.

Once it was destroyed, we’d be at their mercy. Either that or we’d be strongly considering our nuclear options. That said, anything that caused us to commit the 21st century British Expeditionary Force would almost certainly trigger the NATO mutual defence clauses. So there would be more than just the UK involved.

What does 2% Buy in Defence?

Britain is signed up to the NATO commitment to spend 2% of our GDP on Defence. Through some accounting adjustments we spend almost exactly 2% including some overseas aid. The actual defence budget of £38bn for MoD is likely to be about 1.9% of GDP this year. Almost 40% of that is spent on acquiring equipment, notably the aircraft carriers[2], trident submarines and F-35s. Between these three huge ticket items there isn’t much capital left.

As at 1 April 2016[3], the British Army had a trained strength of 79,750 regular personnel and 23,030 reserves, lower than it has ever been since before the start of the 20th Century. The Royal Navy and RAF both had slightly over 32k each, for a total armed forces trained strength of 168k personnel (very few of whom are reserves).

MOD reported that in 2015-16 it spent the following on each of the services[4]:

| Service | Operating Costs | Equipment | Total | Share of Budget |

| Royal Navy | £2.5bn | £3.3bn | £5.8bn | 17.3% |

| Army | £6.6bn | £1.5bn | £8.0bn | 24.0% |

| Royal Air Force | £2.5bn | £3.6bn | £6.1bn | 18.1% |

| Joint Services | £1.9bn | £2.2bn | £4.1bn | 12.2% |

You’ll notice that the totals don’t add up to the whole Defence budget, but that’s because I’ve left out the civilian elements and the long-term strategic acquisitions.

Mass Mobilisation of Our Armed Forces

There’s two ways to look at this, one is a simple uprating of what we currently have by the amount of extra money we might be able to spend and decide whether that would be effective. The other is to look at what we might need and then see if we can afford it.

For either of these tests you need to have an adversary in mind. When you get into it, quality and will to fight affect the answer. It’s not completely about raw numbers. Maybe someone somewhere has done the work to compare the economic strengths of warring powers and what that tells you about outcomes. I doubt it’s clear cut that the bigger economy always wins, but as a general rule it works.

What could we afford?

Britain is currently the 5th biggest spender on Defence worldwide, and our economy is 5th or 6th dependent on currency fluctuations and Brexit impacts. So there aren’t many countries that ought to be able to scare us, even if we can’t field enough troops to round up their military.

The UK GDP in 2016 is around £1.9 trillion[5]. During WW2 we spent over 50% of GDP on the war effort[1]. We taxed people more, borrowed heavily, and the economy also grew significantly from the war expenditure. I’m not sure that we could quite get to 55% on Defence, we’d still have the welfare state to fund, albeit some of it could be diverted to the war effort. We could also up the total tax share from around 37% (according to Treasury’s analysis the public sector spent £713bn in 2015-16[6]) to match that WW2 55%. That could bring Defence spending to 20% of GDP.

Other sources of funding:

- The Welfare budget The UK spends about £250bn on welfare[6], over a third of our public expenditure. Most of it is on pensions and disability, neither of which would reduce as a result of a world war. We do spend £3bn of it on unemployment benefits, and another £27bn on Housing Benefit, both of which might come down a little if there was mass mobilisation. We could perhaps squeeze 0.1% of GDP out of the UK welfare budget.

- The NHS At £162bn annually[6] this is the next largest chunk of public expenditure. At best some of the NHS will become defence medical assets, and the people will transfer to support those we’ve mobilised. Not to mention the inevitable casualties. In practice we’d probably need to spend more on the NHS, or make some really tough choices about priorities.

- Borrowing – in 2015-16 we spent £45bn[6] on debt interest. If we borrowed enough to capitalise the interest for the duration of the war then we could add this amount to Defence budget.

- Efficiency Gains If the rest of government was asked to cut around 10% of their budgets then we could perhaps add another 3% of GDP to the war budget.

So where does all this get us to? About twelve times the current defence budget, so we could significantly increase the size of our armed forces. On a straight multiple that would give us about two million all ranks from mass mobilisation. However I expect more of them would go into the army than either the RN or RAF for the simple reason that it will take longer to produce ships and aircraft to support that level of expansion than it would to produce army equipment.

Britain’s approach to World Wars

Historically we have form. Britain doesn’t maintain its armed forces between major wars. We keep a training cadre and enough to cope with the various small wars we get involved in. When the big war happens we do mass mobilisation of reserves and recruit anyone we can find. Typically it takes 18 months for us to form the million plus citizen armies we need to stand alongside our allies.

Many people (especially civilian politicians and voters) probably consider the idea of a major war very unlikely. We felt the same in the 1920s. Further, they probably also consider that if one did start that it would go nuclear (or find a diplomatic peace) well before we could train and equip the recruits to expand our armed forces. During the Cold War this was almost certainly true.

Infrastructure Deficit

What it means is that we’ve given up on necessary infrastructure to do mass mobilisation. We’ve stopped building military aircraft and tanks in the UK. We’d also struggle with a lot of other equipment, like small arms. Our wider manufacturing base is also shot, so the scope for repurposing factories to scale up production is also limited.

As an example, the British Army writes off small arms on a 10 to 15 year period. That means that normal production will be about a tenth of the current size of the armed forces need. So if everyone needs a rifle then we need 200k rifles for the regular and reserve. Let’s say we have a factory that makes 20k rifles a year, just to replace worn out stocks. When you scale up your armed forces through mass mobilisation to 2 million trained personnel then you suddenly need to build 1.8m extra rifles in under six months, and increase replacement levels to cover expected losses from accidents and combat.

Manufacturing Capacity

We’d also need to find plant, machinery and skilled people to set up factories to produce gun barrels, armour, heavy vehicles, jet engines, aircraft and the complex electronics that make them all work. We’ve got some capacity just now, but it’s all based on small orders delivered over a decade and sharing with other states.

Unlike WW2 the UK doesn’t have broad manufacturing capacity that can be diverted to war production. The UK economy is dominated by service industries, mainly banking. Manufacturing accounts for less than 10% of the UK economy (compared to almost 80% from services).

The extra kit would be a 50% growth in total manufacturing capacity, more like 10-15 times in the specific industries that could produce it. There would also need to be a massive upgrade to chemical & electronics plants to produce military ordnance. It would need to do this almost overnight, we’d need more kit for training people, never mind fighting a war.

Conclusion

There’s room in the British economy for a significant increase in military spending if we faced an existential threat. There’s no political will to spend more than the 2% we’ve committed to via NATO.

The UK doesn’t have the economic base to support significantly increasing manufacturing to equip a scaled up armed force. Nor do we appear to have sufficient spare kit in stock.

Overall, I’d say that we’d need at least a couple of years run up to mass mobilisation. If it ever happens then I hope we get that long. In the meantime, we could do with investing in our manufacturing base. That would make it easier to gear up, and also grow our economy. A strong economy is a better indicator of strength than defence spending.

Notes

[1] Broadberry & [xx], Table 1, pg23, http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/sbroadberry/wp/totwar3.pdf [return]

[2] NB the cost of the carriers isn’t just for the carriers, but also all the rest of the ships needed to support and protect them. [return]

[3] MOD Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/558559/MoD_AR16.pdf [return]

[4] MOD Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16, pgs.137-8 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/558559/MoD_AR16.pdf [return]

[5] Statista, UK GDP at current market prices, https://www.statista.com/statistics/281744/gdp-of-the-united-kingdom-uk-since-2000/ [return]

[6] HM Treasury, Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses 2016, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/538793/pesa_2016_web.pdf [return]