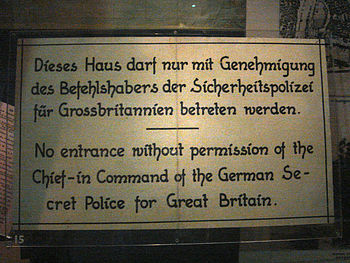

Last Saturday I was political control for the megagame Don’t Panic. As mentioned previously this is a what if megagame about the German Invasion of Britain in 1940. The scenario necessarily changes history to remove some of the most obvious reasons why the Germans didn’t ever try this during WW2.

Anyway my role was to keep an eye on the British war cabinet and ensure that they stayed suitably strategic and global while still providing input to the player teams at Command and Corps level. The game needs some player induced friction from the top, especially when Churchill has a wizard wheeze and send a Division Commander one of his famed ACTION THIS DAY notes.

The structure of the megagame was in two parts. From arrival until 1230 was a planning session simulating July and August 1940. Following that the German invasion lands in early September, and the game moves to 12 hour turns every 40 minutes or so.

Don’t Panic Political Game

The political game started pretty much on arrival for the players, before even the plenary briefing. I had a stack of laminated political event cards to throw in if the war cabinet looked less busy or was spending too much time in the details of the military game. I also had a panic track to keep score of how well the war was going for Britain and how the war cabinet were contributing to that. The panic track was on a 100 point scale and started at 50. Every 10 points the British got a modifier to their supply state depending on the direction of travel.

At the very start of the game I put some ground rules down for the war cabinet players.

- There needed to be an official record of all decisions by the war cabinet

- All decisions had to be by consensus, effectively giving everyone present a veto if they were uncomfortable with the direction

- Collective responsibility applied to decisions, failure to abide by that would lose them political capital

- Decisions that were unpopular or against advice required political capital to be spent (which was sometimes returned if the outcome was good)

- Actions that were carried out by other players needed to be communicated by a war cabinet player to the appropriate person to make it happen

Political Discussion

There were some interesting discussions at Cabinet, (I have retained the minutes and will make them available over on Milmud). To start with there was a discussion about the Royal Family. Should they be dispersed or remain in the UK. It was decided that at the very least the King should be seen to remain until the last sensible moment. Other members, especially the two Princesses, would be kept away from likely invasion landing areas and removed from the country if things started to go badly.

The Royal Navy

The next major debate was on the Royal Navy. Sadly Admiral Pound seemed to be asleep for much of this, which would have been OK had it not been for the consequences following the decision to move most of the fleet from Scapa Flow to Portsmouth. The Cabinet Secretary made a number of interjections to the debate and attempted to put context on the importance of keeping the Kriegsmarine bottled up and the disastrous consequences should the Germans get capital ships in amongst the supply convoys. The politicians in the war cabinet were concerned about the fact that it would take the capital ships at least 24 hours to respond to an invasion across the Channel from Scapa Flow and they couldn’t be sure how well the RAF and army would be able to defend against seaborne assault without naval assistance.

As it turned out (and I listened in to the three way debate with the German Admiral Lutyens) the threat wasn’t as clear to the Germans as it looked to me. Lutyens waited before committing to action, and even then didn’t commit all his resources to breaking out into the Atlantic. Lutyens concern was, rightly for him, that the end result for the Kriegsmarine was likely to be loss of all vessels that they put in the Atlantic. What Lutyens either didn’t seem to realise was that this was potentially a game winning move for the Germans. His fleet unchecked in the Atlantic caused supply difficulties for the British. It also increased the panic track by 3 points every turn.

Once the German fleet was out it created all sorts of bother for the war cabinet. They debated moving Force H out Gibraltar, and more Cabinet Secretary intervention was required to ensure the war cabinet was properly advised. It was about that point that the Italians started their offensive in North Africa…

German Invasion

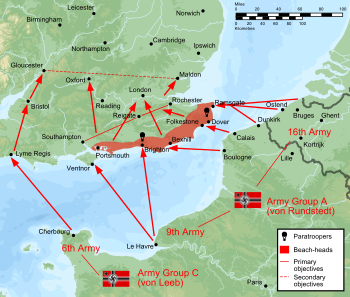

The Germans invaded on a fairly narrow front, about 40km, in the Brighton to Portsmouth area. A planning failure (they didn’t follow the orders they’d been given) meant that they didn’t have enough transport units in the first wave, so they couldn’t move supplies inland. This limited the operating radius of the landed troops to about 8km from the beach. Also the Germans sent armour in the first wave, but couldn’t unload any of it without a port (which was clear in the briefings).

To help things further along the RAF got air superiority over the channel fairly rapidly, and unlike the Royal Navy, sank a significant proportion of the invasion fleet. The Royal Navy frankly didn’t know whether or not it was coming or going. The army reacted as fast as it could to the landings, but was hampered by a combination of shortage of supplies, rail capacity and their organic speed of movement. Mainly the army was a bit further East than the German landing spot. About this time the Royal Navy lost a battleship to a combination of mines and u-boats, this didn’t help panic levels even though the cabinet suppressed the news.

The panic track went into overdrive at this point, and the war cabinet got quite panicky. Their reaction helped things, although not as much as the RAF shooting down dozens of Luftwaffe and sinking about half of the German transport fleet. About two days into the invasion the front stabilised and the Germans largely became unable to land more troops or supplies. They also stopped making progress inland too. The Royal Navy lost a cruiser in the Channel too, damaging the two German Capital ships and driving them off to Brest.

All through this time I was also throwing political events at the war cabinet, making them worry about the Soviets, Japanese, Italians and the Americans, as well as domestic issues. Churchill spoke to President Roosevelt and Lord Halifax spoke to the Irish foreign minister, neither with any real success, although FDR was sympathetic.

Gradually the British Army started to get a grip of the situation (largely after Churchill personally gripped the senior officers). The RAF helped this with carefully targetted bombing of German Divisional HQs and supply dumps. In Portsmouth the Royal Marines held out although surrounded, aided by naval gunfire support over open sights. Even the Press (10 issues over the afternoon) finally became pro-British with the headline news from an anonymous German commander that their situation was hopeless.