Destructive and Formidable by David Blackmore is a quantitative look at British infantry doctrine using period sources from the British Civil Wars of the seventeenth century up to just before the Napoleonic wars. If anything you can see the constancy, which drove the success in battle of British forces, even when outnumbered.

Destructive and Formidable by David Blackmore is a quantitative look at British infantry doctrine using period sources from the British Civil Wars of the seventeenth century up to just before the Napoleonic wars. If anything you can see the constancy, which drove the success in battle of British forces, even when outnumbered.

Development of British Infantry Doctrine

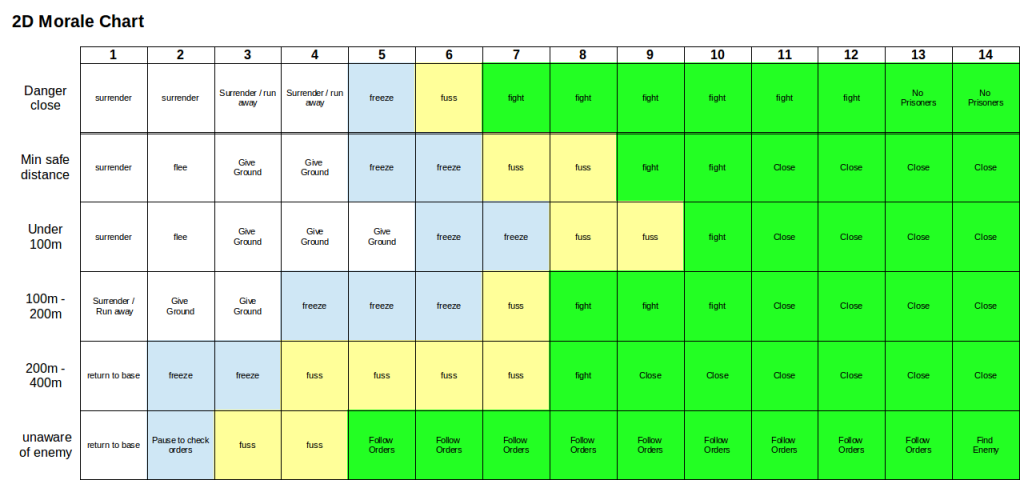

This has got a lot of the detail you need to model infantry battles in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It’s not quite at the level of the WW2 operational research, but it’s good enough. There are comparative weights and rates of fire. Measured hit rates based on range, and commentary on doctrine and how certain tactics worked in certain situations but not others. In short everything you need to design a game (although there’s clearly a morale factor, which Destructive and Formidable covers but makes no attempt to quantify).

There’s a fairly readable style, and the book isn’t long. The examples are of individual battles and focus only on what the British infantry did, their immediate context and the doctrine/tactics of their immediate enemy. The only place there’s anything more in context, and discussion of the commanders impact, is the chapter on the North American irregular wars. This latter chapter also touches on failures of leadership, and shows that there is an effect of good leadership on the successful application of doctrine. The defeats are more attributable to poor leadership and lack of confidence than to failure of doctrine.

Core Infantry Doctrine

The core of British infantry doctrine was to reserve fire until they were close enough to ensure that it was effective. Once fired from close range the British infantry then closed to hand to hand, with clubbed muskets in the early period and bayonets later. Only one or two round were fired, often from a salvee or volley. This kept the effect concentrated, which increased the shock value.

Why didn’t British infantry doctrine spread?

If British infantry doctrine was so successful why did other nations not copy it? Blackmore shows a relative isolation in the British officer corps from the debate of firepower vs shock which European armies seem to have spent the period arguing about. British infantry doctrine seems to have developed by trial and error during the British civil wars to get decisive battles based on the available people and technology. Early civil war battles were inconclusive, yet the British on both sides strove to improve effectiveness. They got closer before opening fire, massed to fire salvos and closed with the enemy to finish them off. Europe spent the same period in the Thirty Years War yet never came to the same conclusion. Drill manuals from the period emphasise fire, the cavalry doctrine shows shock of impact is what works.

What made the British successful?

My suspicion is one of the main things that keeps the British Army successful in this period is a continuity of experience. From the civil wars there is a near continuous presence of warfare. More importantly the outcome of the civil war is the establishment of a standing army. Even though this is supposed to be temporary, Parliament needs to renew it every year, it remains continuously in being. This means that soldiers pass on their experience to the new recruits, and many officers are professionals. Serving in one war as juniors and returning to later wars as commanders of battalions and armies.

Designing a game

My copy of this is flagged in many places, and there are a lot of marginal notations. I fully expect to use it as the core of an infantry combat model for one or more games. There’s a good model explained in the book. Maximum effective range is about 80 yards, at 100 yards less than 1% of shots result in a casualty. At 25-30 yards about a quarter of shots cause casualties. Closing with the enemy is pretty much always decisive (they either break or die). Infantry firing by platoon can stop cavalry with firepower alone if they reserve fire until the cavalry is about 30 yards away. Similarly if you fire at charging Highlanders at about 10 yards (or less) then it ends the charge…

This is an edited version of a post that was first published at https://www.themself.org/2019/01/destructive-formidable-david-blackmore-review/